14 to 2 seconds: how I improved the performance of an endpoint by 82% - part 2

Language details may impact application performance. In this article we’ll see some of the C# tips that brought me to improve my application. Singleton creation, StringBuilder and more!

Table of Contents

Just a second! 🫷

If you are here, it means that you are a software developer. So, you know that storage, networking, and domain management have a cost .

If you want to support this blog, please ensure that you have disabled the adblocker for this site. I configured Google AdSense to show as few ADS as possible - I don't want to bother you with lots of ads, but I still need to add some to pay for the resources for my site.

Thank you for your understanding.

- Davide

In this second article, I’m going to share some more tips that brought me to improve the performance of an API from 14sec to less than 3 seconds: an improvement of 82%.

In the previous article, we’ve seen some general, language-agnostic ways to approach this kind of problem, and what you can try (and avoid) to do to achieve a similar result.

In this article, we’re going to see some .NET-related tips that can help to improve your APIs performance.

WarmUp your application using Postman to create Singleton dependencies

In my application, we use (of course) dependency injection. Almost all the dependencies are marked ad Singleton: this means that every dependency is created at the start-up of the application and is then shared through all the lifespan of the application.

Pss: if you want to know the difference between Singleton, Transient, and Scoped lifetimes with real examples, check out this article!

It makes sense, right? But have a closer look at the timing in this picture:

The blue line is the whole HTTP call, and the black line is the API Action.

There are almost 2 seconds of nothing! Why?

Well, as explained in the article “Reducing initial request latency by pre-building services in a startup task in ASP.NET Core” by Andrew Lock, singletons are created during the first request, not at the real start-up of the application. And, given that all the dependencies in this application are singletons, the first 2 seconds are being used to create those instances.

While Andrew explains how to create a Startup task to warm up the dependencies, I opted for a quick-and-dirty option: create a Warmup endpoint and call it before any call in Postman.

[HttpGet, Route("warmup")]

public ActionResult<string> WarmUp()

{

var obj = new

{

status = "ready"

};

return Ok(obj);

}

It is important to expose that endpoint under a controller that uses DI: as we’ve seen before, dependencies are created during the first request they’re needed; so, if you create an empty controller with only the WarmUp method, you won’t build any dependency and you’ll never see improvements. My suggestion is to place the WarmUp method under a controller that requires one of the root services: in this way, you’ll create the services and all their dependencies.

To call the WarmUp endpoint before every request, I’ve created this simple script:

pm.sendRequest("https://localhost:44326/api/warmup", function (err, response) {

console.log("ok")

})

So, if you paste it in Postman, into the Pre-requests Script tab, it executes this call before the main HTTP call and warms up your application.

This tip will not speed up your application but gives your a more precise value for the timings.

Improve language-specific details

Understanding how C# works and what functionalities it offers is crucial to get well working applications.

There’s plenty of articles around the Internet that tell you some nice tips and trick to improve .NET performance; here I’ll list some of my favorite tips an why you should care about them.

Choose the correct data type

There’s a lot you can do, like choosing the right data type: if you are storing a player’s age, is int the right choice? Remember that int.MinValue is -2147483648 and int.MaxValue is -2147483648.

You could use byte: its range is [0,255], so it’s perfectly fine to use it.

To have an idea of what data type to choose, here’s a short recap with the Min value, the Max value, and the number of bytes occupied by that data type:

| Data type | Min value | Max Value | # of bytes |

|---|---|---|---|

| byte | 0 | 255 | 1 |

| short | -32768 | 32767 | 2 |

| ushort | 0 | 65535 | 2 |

| int | -2147483648 | 2147483647 | 4 |

| uint | 0 | 4294967295 | 4 |

So, just by choosing the right data type, you’ll improve memory usage and then the overall performance.

It will not bring incredible results, but it’s a good idea to think well of what you need and why you should use a particular data type.

StringBuilder instead of string concatenation

Strings are immutable, in C#. This means that every time you concatenate 2 strings, you are actually creating a third one that will contain the result.

So, have a look at this snippet of code:

string result = "<table>";

for (int i = 0; i < 19000; i++)

{

result += "<tr><td>"+i+"</td><td>Number:"+i+"</td></tr>";

}

result += "</table>";

Console.WriteLine(result);

This loop took 2784 milliseconds.

That’s where the StringBuilder class comes in handy: you avoid all the concatenation and store all the substrings in the StringBuilder object:

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

result.Append("<table>");

for (int i = 0; i < 19000; i++)

{

result.Append("<tr><td>");

result.Append(i);

result.Append("</td><td>Number:");

result.Append(i);

result.Append("</td></tr>");

}

result.Append("</table>");

Console.WriteLine(result.ToString());

Using StringBuilder instead of string concatenation I got the exact same result as the example above but in 58 milliseconds.

So, just by using the StringBuilder, you can speed up that part by 98%.

Don’t return await if it’s the only operation in that method

Every time you mark a method as async, behind the scenes .NET creates a state machine that keeps track of the execution of each method.

So, have a look at this program where every method returns the result from another one. Pay attention to the many return await statements;

async Task Main()

{

var isAvailable = await IsArticleAvailable();

Console.WriteLine(isAvailable);

}

async Task<bool> IsArticleAvailable()

{

var articlePath = "/blog/clean-code-error-handling";

return await IsPathAvailable(articlePath);

}

async Task<bool> IsPathAvailable(string articlePath)

{

var baseUrl = "https://www.code4it.dev/";

return await IsResourceAvailable(baseUrl, articlePath);

}

async Task<bool> IsResourceAvailable(string baseUrl, string articlePath)

{

using (HttpClient client = new HttpClient() { BaseAddress = new Uri(baseUrl) })

{

HttpResponseMessage response = await client.GetAsync(articlePath);

return response.IsSuccessStatusCode;

}

}

So, what did I mean with state machine?

Here’s just a small part of the result of the decompilation of that code. It’s a looooong listing: don’t focus on the details, just have a look at the general structure:

If you are interested in the full example, here you can find the gist with both the original and the decompiled file.

internal static class <Program>$

{

private sealed class <<<Main>$>g__Main|0_0>d : IAsyncStateMachine

{

public int <>1__state;

public AsyncTaskMethodBuilder <>t__builder;

private bool <isAvailable>5__1;

private bool <>s__2;

private TaskAwaiter<bool> <>u__1;

private void MoveNext()

{

int num = <>1__state;

try

{

TaskAwaiter<bool> awaiter;

if (num != 0)

{

awaiter = <<Main>$>g__IsArticleAvailable|0_1().GetAwaiter();

if (!awaiter.IsCompleted)

{

num = (<>1__state = 0);

<>u__1 = awaiter;

<<<Main>$>g__Main|0_0>d stateMachine = this;

<>t__builder.AwaitUnsafeOnCompleted(ref awaiter, ref stateMachine);

return;

}

}

else

{

awaiter = <>u__1;

<>u__1 = default(TaskAwaiter<bool>);

num = (<>1__state = -1);

}

<>s__2 = awaiter.GetResult();

<isAvailable>5__1 = <>s__2;

Console.WriteLine(<isAvailable>5__1);

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

<>1__state = -2;

<>t__builder.SetException(exception);

return;

}

<>1__state = -2;

<>t__builder.SetResult();

}

void IAsyncStateMachine.MoveNext()

{

//ILSpy generated this explicit interface implementation from .override directive in MoveNext

this.MoveNext();

}

[DebuggerHidden]

private void SetStateMachine(IAsyncStateMachine stateMachine)

{

}

void IAsyncStateMachine.SetStateMachine(IAsyncStateMachine stateMachine)

{

//ILSpy generated this explicit interface implementation from .override directive in SetStateMachine

this.SetStateMachine(stateMachine);

}

}

private sealed class <<<Main>$>g__IsArticleAvailable|0_1>d : IAsyncStateMachine

{

public int <>1__state;

public AsyncTaskMethodBuilder<bool> <>t__builder;

private string <articlePath>5__1;

private bool <>s__2;

private TaskAwaiter<bool> <>u__1;

private void MoveNext()

{

int num = <>1__state;

bool result;

try

{

TaskAwaiter<bool> awaiter;

if (num != 0)

{

<articlePath>5__1 = "/blog/clean-code-error-handling";

awaiter = <<Main>$>g__IsPathAvailable|0_2(<articlePath>5__1).GetAwaiter();

if (!awaiter.IsCompleted)

{

num = (<>1__state = 0);

<>u__1 = awaiter;

<<<Main>$>g__IsArticleAvailable|0_1>d stateMachine = this;

<>t__builder.AwaitUnsafeOnCompleted(ref awaiter, ref stateMachine);

return;

}

}

else

{

awaiter = <>u__1;

<>u__1 = default(TaskAwaiter<bool>);

num = (<>1__state = -1);

}

<>s__2 = awaiter.GetResult();

result = <>s__2;

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

<>1__state = -2;

<articlePath>5__1 = null;

<>t__builder.SetException(exception);

return;

}

<>1__state = -2;

<articlePath>5__1 = null;

<>t__builder.SetResult(result);

}

void IAsyncStateMachine.MoveNext()

{

//ILSpy generated this explicit interface implementation from .override directive in MoveNext

this.MoveNext();

}

[DebuggerHidden]

private void SetStateMachine(IAsyncStateMachine stateMachine)

{

}

void IAsyncStateMachine.SetStateMachine(IAsyncStateMachine stateMachine)

{

//ILSpy generated this explicit interface implementation from .override directive in SetStateMachine

this.SetStateMachine(stateMachine);

}

}

[AsyncStateMachine(typeof(<<<Main>$>g__IsArticleAvailable|0_1>d))]

[DebuggerStepThrough]

internal static Task<bool> <<Main>$>g__IsArticleAvailable|0_1()

{

<<<Main>$>g__IsArticleAvailable|0_1>d stateMachine = new <<<Main>$>g__IsArticleAvailable|0_1>d();

stateMachine.<>t__builder = AsyncTaskMethodBuilder<bool>.Create();

stateMachine.<>1__state = -1;

stateMachine.<>t__builder.Start(ref stateMachine);

return stateMachine.<>t__builder.Task;

}

Every method marked as async “creates” a class that implements the IAsyncStateMachine interface and implements the MoveNext method.

So, to improve performance, we have to get rid of lots of this stuff: we can do it by simply removing await calls when there is only one awaited method and you do nothing after calling that method.

So, we can transform the previous snippet:

async Task Main()

{

var isAvailable = await IsArticleAvailable();

Console.WriteLine(isAvailable);

}

async Task<bool> IsArticleAvailable()

{

var articlePath = "/blog/clean-code-error-handling";

return await IsPathAvailable(articlePath);

}

async Task<bool> IsPathAvailable(string articlePath)

{

var baseUrl = "https://www.code4it.dev/";

return await IsResourceAvailable(baseUrl, articlePath);

}

async Task<bool> IsResourceAvailable(string baseUrl, string articlePath)

{

using (HttpClient client = new HttpClient() { BaseAddress = new Uri(baseUrl) })

{

HttpResponseMessage response = await client.GetAsync(articlePath);

return response.IsSuccessStatusCode;

}

}

into this one:

async Task Main()

{

var isAvailable = await IsArticleAvailable();

Console.WriteLine(isAvailable);

}

Task<bool> IsArticleAvailable()

{

var articlePath = "/blog/clean-code-error-handling";

return IsPathAvailable(articlePath);

}

Task<bool> IsPathAvailable(string articlePath)

{

var baseUrl = "https://www.code4it.dev/";

return IsResourceAvailable(baseUrl, articlePath);

}

async Task<bool> IsResourceAvailable(string baseUrl, string articlePath)

{

using (HttpClient client = new HttpClient() { BaseAddress = new Uri(baseUrl) })

{

HttpResponseMessage response = await client.GetAsync(articlePath);

return response.IsSuccessStatusCode;

}

}

Notice that I removed both async and await keywords in the IsArticleAvailable and IsPathAvailable method.

So, as you can see in this Gist, the only state machines are the ones for the Main method and for the IsResourceAvailable method.

As usual, the more we improve memory usage, the better our applications will work.

Other stuff

There’s a lot more that you can improve. Look for articles that explain the correct usage of LINQ and why you should prefer HttpClientFactory over HttpClient.

Run operations in parallel - but pay attention to the parallelism

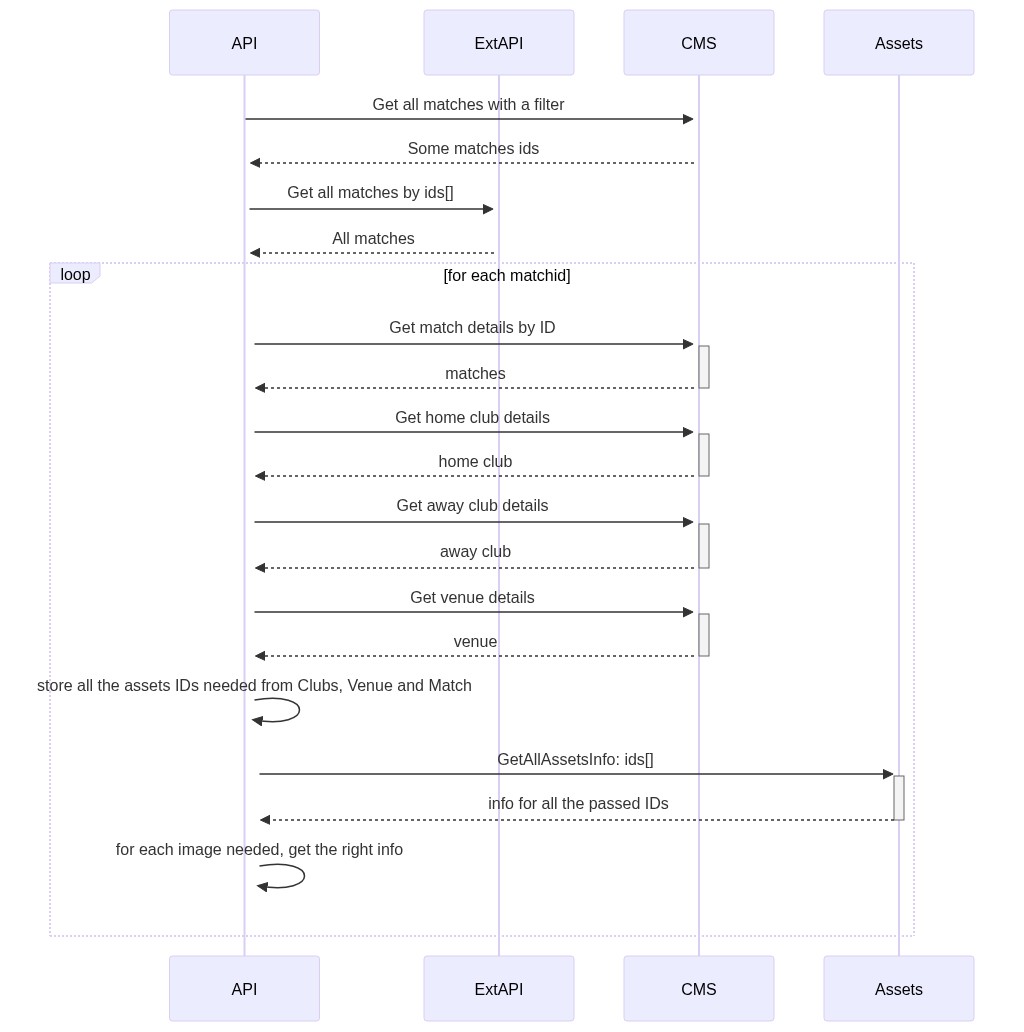

Let’s recap a bit what problem I needed to solve: I needed to get some details for a list of sports matches:

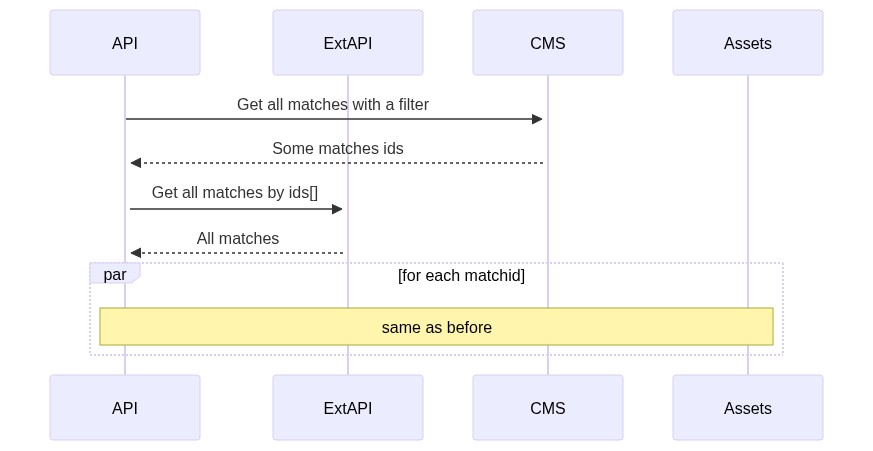

As you see, I perform the same set of operations for every match. Working on them in parallel improved a bit the final result.

Honestly, I was expecting a better improvement. Parallel calculation is not the silver bullet. And you should know how to implement it.

And I still don’t know.

After many attempts, I’ve created this class that centralizes the usage or parallel operations, so that if I find a better way to implement it, I just need to update a single class.

Feel free to copy it or suggest improvements.

public static class ParallelHelper

{

public static IEnumerable<Out> PerformInParallel<In, Out>(IEnumerable<In> items, Func<In, Out> fn, int maxDegreeOfParallelism = 10)

{

var options = new ParallelOptions { MaxDegreeOfParallelism = maxDegreeOfParallelism };

ConcurrentBag<Out> cb = new ConcurrentBag<Out>();

Parallel.ForEach(items, options, item =>

{

cb.Add(fn(item));

});

return cb.ToList();

}

public static IEnumerable<Out> PerformInParallel<In, Out>(IEnumerable<IEnumerable<In>> batches, Func<In, Out> fn, int maxDegreeOfParallelism = 10)

{

var options = new ParallelOptions { MaxDegreeOfParallelism = maxDegreeOfParallelism };

ConcurrentBag<Out> cb = new ConcurrentBag<Out>();

foreach (var batch in batches)

{

Parallel.ForEach(batch, options, item =>

{

cb.Add(fn(item));

});

}

return cb.ToList();

}

public static IEnumerable<Out> PerformInParallel<In, Out>(IEnumerable<IEnumerable<In>> batches, Func<IEnumerable<In>, IEnumerable<Out>> fn, int maxDegreeOfParallelism = 10)

{

var options = new ParallelOptions { MaxDegreeOfParallelism = maxDegreeOfParallelism };

ConcurrentBag<Out> cb = new ConcurrentBag<Out>();

Parallel.ForEach(batches, options, batch =>

{

var resultValues = fn(batch).ToList();

foreach (var result in resultValues)

{

cb.Add(result);

}

});

return cb.ToList();

}

}

The first method performs the operation specified in the Func on every item passed in the IEnumerable parameter: then it aggregates the result in the ConcurrentBag object (it’s a thread-safe collection) and then returns the final result.

The other methods do a similar thing but to a list of lists: this is useful when splitting the calculation into batches and performing each of these batches in sequence.

But, why the MaxDegreeOfParallelism? Well, resources are not infinite; you can’t perform the same heavy operation on 200000 items at the same time, even more, if many requests arrive simultaneously. You have to reduce the number of items processed in parallel.

In the picture above you can see the parallel execution of the search for assets: every call begins at the same moment, so the final timing is a lot better than if I had performed all the operations in sequence.

Move to .NET 5

As reported by the official documentation, there has been a huge improvement in performance in the latest version of .NET.

Those improvements are mainly about the usage of Garbage Collector, JIT optimization, and usage of strings and Regex-s.

If you are interested, here’s a good article on Microsoft’s blog.

So, did it really improved my application?

Well, no.

As you already know, the main bottlenecks are because of external dependencies (aka API calls). So, nothing that an update of the whole framework could impact.

But, just to try it, I moved my application from .NET Core 3.1 to .NET 5: the porting was incredibly easy. But, as I was expecting, I did not get any significant improvement.

So, since the application was a dependency of a wider system, I rolled it back to .NET 3.1.

Ask, discuss, communicate

The last tip is one of the most simple yet effective ones: talk with your colleagues, keep track of what worked and what didn’t, and communicate with other developers and managers.

Even if a question is silly, ask. Maybe you’ll find some tip that gives you the best idea.

Have a call with your colleagues, share your code and let them help you: even a simple trick, a tool they can suggest, an article that solves one of your problems, can be the key to the success.

Don’t expect any silver bullet: you’ll improve your application with small steps.

Wrapping up

We’ve seen how I managed to improve the performance of an API endpoint passing from 14 seconds to 3.

In this article you’ve seen some .NET-related tips to improve the performance of your applications: nothing fancy, but those little steps might help you reach the desired result.

Of course, there is more: if you are want to know how compression algorithms and hosting models affect your applications, check out this article!

If you have more tips, feel free to share them in the comments session!

Happy coding!